“Trumpism,” our issue focusing on the global right, is out now. Subscribe to our print edition at a discounted rate today.

The story of the Dunnes Stores strike, when it’s told, often begins on July 19, 1984, with a woman approaching a supermarket till on Dublin’s Henry Street. Mary Manning, the twenty-one-year-old sitting behind the till, tells the woman that she can’t handle the two grapefruits in her basket because she’s following an instruction from her trade union to boycott goods from apartheid South Africa. Manning is then sent up to the manager’s office, where she’s given the opportunity to change her mind. When she refuses, she’s suspended, and nine of her colleagues — Karen Gearon, Cathryn O’Reilly, Tommy Davis, Theresa Mooney, Veronica Munroe, Sandra Griffin, Alma Russell, Michelle Gavin, and Liz Deasy, all between the ages of seventeen and twenty-eight — walk out alongside her and onto a picket line.

But the truth is that the events of the strike had been set in motion long before that day. “We were following a union instruction because we had been treated so badly in work,” Karen Gearon says. Gearon, now in her sixties, was the Irish Distributive and Administrative Trade Union (IDATU) shop steward for the Henry Street Dunnes in 1984 and Mary Manning’s best friend. “If we had been working in a nice environment, would we have taken that union instruction seriously? I don’t know. Probably not.”

The grievances of the workers and IDATU members — most of them women — against the managers at Dunnes — most of them men — were already manifold in July 1984. They were only allowed two toilet breaks of eight minutes each per day, despite the toilet being eight floors up; their bags would be searched when they left the shop and a point made of embarrassing them if pads or tampons were found; there were allegations of sexual harassment. In an interview on Raidió Teilifís Éireann (RTÉ) from 1984, Gearon recalls seeing “young girls crying because the management have intimidated and upset them.”

In this hostile context, the union directive was seen by both workers and managers as an opportunity for confrontation; the situation in South Africa was by the by. In Striking Back, her 2018 book cowritten with Sinead O’Brien, Mary Manning describes coming to work that July morning and realizing that managers had been drafted in from other stores — and that every worker put on the tills was a member of IDATU.

When the workers went out, then, they were driven not by a position on apartheid but by a desire to put two fingers up to Dunnes management. Manning is frank: she couldn’t spell “apartheid” at that point, she writes, let alone explain its meaning. It’s an irony emphasized in Strike!, Tracy Ryan’s 2021 play about the Dunnes Stores story. “The strikers have always been very honest about that,” Ryan says. “But they quickly understood what they were doing and became committed to it.”

The shift began when Nimrod Sejake arrived on the picket line less than a week into the strike. Before claiming asylum in Ireland, Sejake had been a teacher, a trade unionist, and an activist for the African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa. Forced to leave in 1962 after being tried for treason alongside Nelson Mandela, by 1984 he was living in a Red Cross hostel four miles from Henry Street. For most of the strikers, he was the first black person they had ever met.

“When you have real-life experiences shared with you, it makes a difference,” Gearon says. Sejake began attending the pickets every day and, while there, describing to the strikers the realities of apartheid — the denial of civil liberties to the black majority, the enforced destitution, the exploitation, and the killing. One allegory he used is mentioned in several accounts of the strike: that apartheid South Africa was like a pint of Guinness, with the white sitting firmly on top of the black. He also told them about the family he had left behind, including three children not seen for twenty years.

On the strike’s first day, the ten had been told by their union organizer, Brendan Archbold — himself a member of the Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement (IAAM) and who would remain key to the strike until its end — that they would receive strike pay of just £21 per week while out. They had persisted on the basis that they only expected the strike to last a couple of weeks. Sejake’s testimonies raised the stakes.

“It was just wrong, what they were learning about,” says Ryan. “You see it now with the student encampments for Palestine. You can’t unlearn these things. It was the same for the strikers — it changed their perspectives completely.” Quickly, what had begun as a “screw you” to spiteful bosses became something much bigger. Manning and her colleagues were decided: they weren’t going back until they never had to handle apartheid produce again.

The IAAM had been founded in 1962 by Kader Asmal, an ANC member and law lecturer at Trinity College Dublin. By 1984, it was a powerful campaign with members including John Mitchell, general secretary of IDATU, and Ruairi Quinn, minister for labor in Ireland’s Fine Gael–Labour coalition government. Asmal was quick to visit the picket line in the hot summer of 1984, taking interviews from the press and offering the Dunnes strikers the organization’s support. As the strike progressed, other organizing groups would also provide picket-line support, including Labour Youth, Sinn Fein, Action from Ireland (Afri), and the dockers’ union, which in August 1984 led a parade down Henry Street.

Manning and her colleagues were decided: they weren’t going back until they never had to handle apartheid produce again.

The response from the broader public, however, was often critical and tinged with the belief that a group of young working-class people, the majority women and two single mothers, had no place meddling in the complexities of international politics — particularly when they were already lucky to have good-paying jobs in recession-hit Ireland. Some assumed they had to be the stooges of political actors with ulterior motives. In response, the strikers — none of whom had been involved in politics before — agreed not to become part of any activist group or political party until their action was over. “The media did want to portray us as this militant, left-wing bunch of young people controlled by others,” says Karen. “But I think as time went on and they got to know us they realized that we were ordinary young people not involved in anything, that we just happened to be doing something quite extraordinary.”

Harder to bear than criticism from the public — alongside the racist taunts and occasional old food thrown from the windows of Dunnes by colleagues — were the disappointments caused by important figures who ostensibly shared the strikers’ focus on equality. It became clear, for example, that John Mitchell was a rarity on the IDATU executive when Brendan Archbold told the ten that although the union would commit to the £21 per week, they would not give formal encouragement to an all-out strike.

Bishop Eamonn Casey, then an influential figure in the church, also expressed private disapproval of the strike, and some priests even encouraged their congregants to cross the picket line from the pulpit on the basis that the strike was doing harm to black South African workers and that the Dunnes were a good Catholic family. Ruairi Quinn claimed he could not get involved in the dispute because it was an industrial issue, not a political one, and directed the strikers and Dunnes toward the labor court. Worst of all, by October 1984, Kader Asmal had informed the strikers that he was withdrawing his support from their action — that it had, in his eyes, gone on long enough.

To underscore their isolation as summer turned to winter, the strikers also found themselves facing growing hostility from the police. To avoid the daily pickets, the Henry Street store had begun bringing in its goods via a rubbish removal company overnight — one example of the intransigence that Ben Dunne, director of the family company, showed toward the action until its end. When the strikers realized what was happening, they started holding all-night pickets. In the darkness of the quiet street, the Gardaí proved more willing to use aggression to get the strikers out of the trucks’ path: in one case, Manning recalls in her book, the police — three of them to each striker — charged at the picket, separated them, forced some up against the wall of the building, and left them “battered and bruised.” After another late-night delivery, Tommy Davis, the only man in the group, was arrested, beaten, and then charged with breach of the peace. In late 1984 and early 1985, Theresa Mooney and Cathryn O’Reilly were both visited at their homes by Special Branch officers.

“None of us had been in trouble with the law before. We went through a horrific time with the police when I think of it,” Karen says. And yet, she continues, their focus remained with the people in South Africa facing far worse for the crime of being born black. “How can people treat people like that because of the color of their skin?” she asks. Such moral insults were evidently not a concern for the guards. Cathryn O’Reilly, in the 2014 documentary Blood Fruit, recalls one officer, who had just hauled her out of the way on a night picket, pointing to a ring on his finger and declaring it was “good South African gold.”

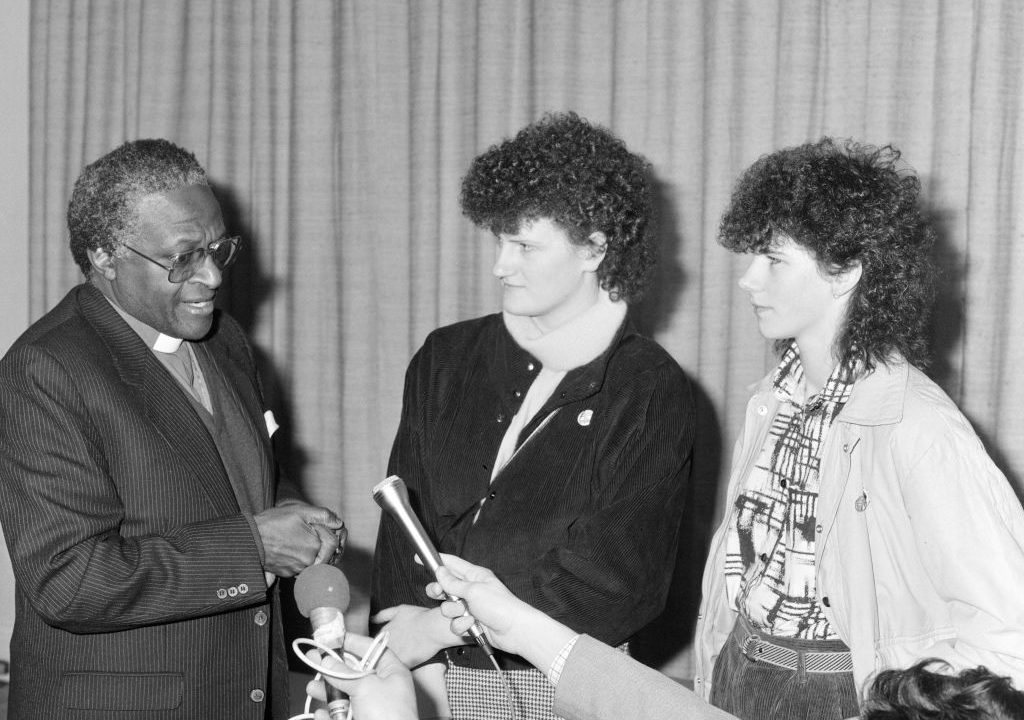

What the Irish establishment perhaps should’ve foreseen was that these attacks garnered publicity, and not just in Ireland. The first real breakthrough had come in August 1984, when Archbishop Desmond Tutu, en route to Oslo to collect his Nobel Peace Prize, requested a meeting with the strikers. Manning and Gearon took the ferry over to England. “Within two minutes,” Manning writes, “this hugely powerful and influential man had given us more validation than anybody in Ireland since the beginning of our action.”

In the summer of 1985, an invitation arrived from Tutu for the strikers to visit South Africa to see the reality of apartheid firsthand. When the IDATU and the IAAM failed to put up the money for the trip (Kader Asmal even tried to claim that the visit breached the cultural boycott), one night of bucket-shaking in Dublin pubs collected £7,000 — proof of a growing sympathy from the Irish public, which had also begun to swell the open picket lines held outside the Henry Street store on Saturdays. By then, a year into the strike, even Bishop Casey had U-turned and commended the strikers on TV.

The visit, however, was not to take place — or not in the way Tutu intended. On arrival at Heathrow, the eight who had agreed to the trip were told their visa-free access to South Africa had been revoked. They were then ushered onto the plane anyway and landed in Johannesburg, only to be escorted into a windowless room and held there — in a country where they knew that activists routinely “disappeared” or were murdered — under armed guard.

‘Our main goal was to highlight apartheid. We genuinely never envisaged that the Irish state would ban the goods from the country.’

Eight terrifying hours later, the group was flying back to Heathrow — but not before Gearon had turned back on the steps up to the plane and declared: “We will be back when South Africa is free!” Asked now what was going through her mind at the time, she is plain. “Going through my head was: they are a bunch of bastards.”

Stoked by the uncertainty over the group’s disappearance, reporters had assembled at Dublin airport to meet them. At the ensuing press conference, Archbold used the title that’s still stuck to the group forty years on: on the basis of their reception in Johannesburg, he said, he was in the presence of the “eight most dangerous supermarket workers” in the world.

If the South African government intended to force the strikers’ submission through intimidation, the opposite happened: the news about the detainment gave the strike its biggest boost yet. The picket on the Saturday after they returned from Johannesburg was attended by thousands. In October 1985, another Dunnes worker from the Crumlin branch, Brendan Barron, joined the strike; the same month, Gearon was invited to address the United Nations (UN) Special Committee Against Apartheid in New York. Her speech was met with the first recorded standing ovation at the UN.

“We know how much was spent by South Africa to put down any kind of criticism of what was going on,” says Ryan. “But once you hit that tipping point, it’s very hard for things to go back.”

By December 1985, it was clear Irish government inaction was no longer tenable, and an investigation was announced into the use of forced labor in the production of South African goods. As Quinn explains in Blood Fruit, free trade principles under what was then the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (now the World Trade Organization) made it illegal for one state to boycott goods from another on political grounds — but a stipulation of the International Labor Organization made such boycotts possible if the goods were the product of slave or prison labor.

The IDATU instructed the strikers to lift the picket while the investigation took place. Together with the knowledge that apartheid produce was still being sold in Dunnes, it was a decision that resulted in one of the lowest periods of the strike. “We felt something was taken away from us,” Gearon says. That feeling was worsened by the fact that John Mitchell had, in September, been quoted in an interview with the Irish Press saying he thought it was time for the Dunnes Stores strikers to go back.

Even if they had wanted to, it was too late. Mary Manning was sitting at the kitchen table with her father in February 1986 when the news came through: the government had completed its investigation and confirmed that prisoners were being hired out to farmers in South Africa as cheap labor. A ban was therefore being put in place from January 1987 with a three-month phaseout period. It meant, Manning writes, “that by April 1987 not one product from South Africa would be on the shelves of an Irish shop.”

Gearon is clear this change didn’t stem from the sudden growth of governmental spines. “If you actually look back in the difference in legislation, they could’ve done that the day after we started the strike,” she says. “No laws changed in the two years and nine months to prevent them from not introducing that same piece of legislation. The only change was us not going away.”

In an act reminiscent of the petty management style that had first sent them to the picket, Ben Dunne was not willing to let the strikers win and return to work without a final knock. On arriving back at Dunnes in January 1987, they were presented with a new contract that committed them to handling everything on sale, including the South African produce that remained. They refused and went out again.

When the strike officially ended on April 12, 1987, the ten had spent two years and nine months out. Each had had to survive on £21 a week for that time; Veronica Munroe had had her home repossessed. And yet the result was far beyond what any of them had imagined they could achieve.

“Our main goal was to highlight apartheid and at least for us to win the right not to handle the goods. We genuinely never envisaged that the Irish state would ban the goods from the country.” Gearon laughs down the phone: “How did we do it? Can we do it again?”

It might’ve been a quiet ending. Not all of the strikers returned to Dunnes or stayed for long: some found new jobs, some emigrated. Gearon went back only to be bullied, sacked, and then blacklisted by employers in Dublin. The idea of celebrating the strike, as Ryan puts it, was a long way off — the focus was on recovery.

The public responded to the news that Irish ministers and statespeople would be attending Nelson Mandela’s funeral with a demand: that the Dunnes Stores strikers go as Ireland’s representatives instead.

That changed in 1990, when the news arrived that a free Nelson Mandela was visiting Ireland and wanted to meet the group. The event was arranged at a Dublin hotel by the Irish Congress of Trade Unions and the IAAM. “We know the sacrifices they underwent — some of them lost their jobs,” Mandela would say when it took place. “But what struck us most was the fact that members of the labor movement so many thousands of miles away from us felt this sense of commitment to the struggle against racial oppression in South Africa.”

“That was the first time we got any recognition,” says Karen. It wasn’t the last. When Mandela died twenty-three years later, the public responded to the news that Irish ministers and statespeople would be attending his funeral with a demand: that the Dunnes Stores strikers go as Ireland’s representatives instead.

“It was an experience that none of us could ever have imagined,’”Gearon continues. She adds that the best part was going to Soweto and meeting the family of Sejake, the man whose resilience had given them so much strength on the picket line, and who had returned to a free South Africa to serve as secretary of the Soweto ANC Veterans League before passing away in 2004.

When Ryan came across the strikers’ story in 2008, she was shocked that it was so little known. “I did wonder if it was because they were working-class and majority women,” she says. Gearon echoes her view: “I think it’s probably the first time since the 1910s or 1920s that women have really taken to the fore in standing up for something as a group. Women’s history has been written out of Ireland to a large extent.”

Although there’s now a road in Soweto called Manning Street and a plaque outside the Henry Street Dunnes commemorating the strike, efforts to draw attention to the fortieth anniversary this year have been difficult, and the funds for a new tour of Strike! in Ireland and the UK have fallen short. Ryan and Ardent, the company that produced a run of the play in London in 2023, are now exploring ways to turn it into an educational resource alongside an information pack available on Ardent’s website. Despite the setback, Ryan is determined that, one way or another, the story be used to inspire other young working-class people and give them a sense of their agency.

As Gearon acknowledges, that inspiration could hardly come at a more important moment. Four decades on from the Dunnes strike, the slaughter of Palestinians by the Israeli state and the complicity of Western governments have galvanized another international movement, this too comprising huge numbers of young people and this too calling for boycotts. The difference today, as Gearon points out, is that the trade union movement is no longer seen — or making itself seen — as a means by which those young people can effect change. Legislative developments like Ireland’s 1991 Industrial Relations Act, which made it illegal for workers to strike on issues of conscience, have narrowed the scope of action available to unions, but she feels there’s also a question of will. “Young people today aren’t seeing leadership — true leadership — from the trade union movement.”

Still, she retains faith that a renewed iteration of that movement will drive the cause of justice. Gearon emphasizes that the trade union was not simply a tool she and her colleagues used to make their stand against apartheid — it was the trade union that compelled them to take that stand and learn about apartheid in the first place. “People need to remember that we did not go out of conscience,” she says.

We went out because we followed a union instruction. If you look at the leadership of the trade union movement in the early ’80s, there was a lot of global solidarity. [Our action] came from our leadership saying, “We want our members not to handle South African goods because the South African trade union movement has asked for their country to be boycotted.” Ours was not a conscientious objection. It was much more than that.

The story of the Dunnes Stores strike generally ends either with the strikers’ victory — forcing Ireland to become the first Western state to boycott goods from apartheid South Africa — or with the strikers’ trip to Mandela’s funeral. But Manning and Gearon’s signatures on a letter to the Irish Times from May this year urging Ireland’s Eurovision entry to boycott the event in solidarity with Palestine make it clear that the struggle of these people and those who backed them for a world of justice is ongoing. The lesson to be learned from it now seems not that they’re extraordinary individuals — although they clearly are — but that the capacity for extraordinary action exists inside everyone who’s ever been pissed off with the bosses. It just takes organization to bring it out.

Republished from Tribune.

Francesca Newton is online editor at Tribune.